Pastry/Prep Chef

Pastry/Prep Chef Salary: £30,000-£33,000 (excluding tips) Tips: Approx. £800+/month Hours: 45 hours per week over five days Location: Knepp Wilding Kitchen, Dial Post, RH13 8PY

Home / March: Old Moss, New Plants

Moy Fierheller | Deputy Head Gardener

Published April 2025

The first day of meteorological spring arrives with textbook cloudless skies, the air crisp, the light sharp. Frosted mornings follow, wreathed with freezing fog, oak and hawthorn rising from the wisps like ghostly phantoms until the sun’s heat shoos away the unwelcome visitor.

The garden is reminiscent of a family Sunday morning – the perennial winter stems sleep on like parents, while small excitable children in the form of snow irises, low growing tulips, dwarf daffodils, winter windflowers and primulas jump out in loud clamouring for attention with bright blues, purple, pinks and yellows.

March is a month of disturbing the ground, planting and seed sowing, when the days begin to lengthen and the soil starts to warm – a dynamic landscape engineering of the garden, mimicking the Tamworth pigs and herbivore herds driving natural processes in the rewilding project.

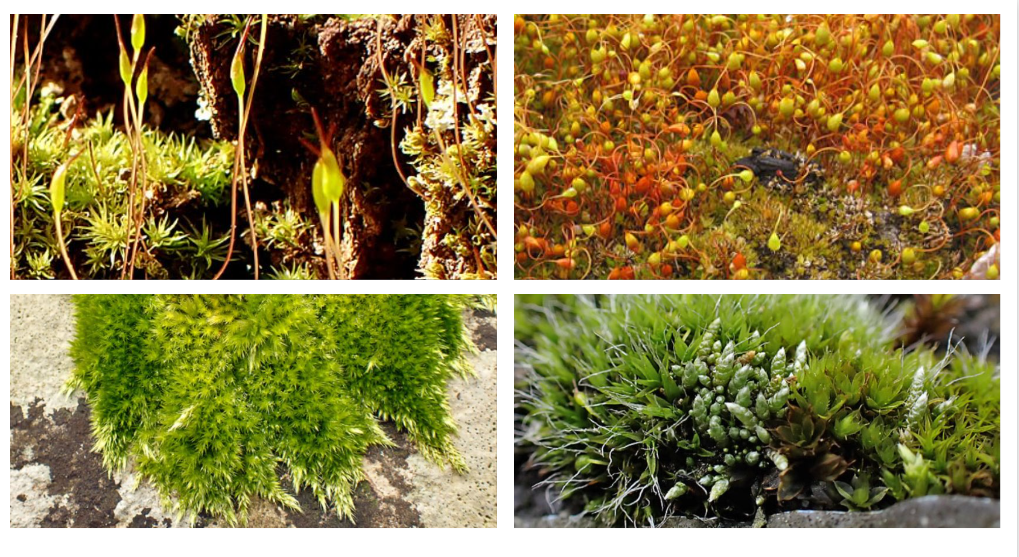

All through the most nutrient-poor, free-draining crushed concrete of the Rewilded Garden’s long ridge designed by James Hitchmough, a proliferation of moss has become dominant. This month, the Sussex Bryophyte Society has been surveying mosses, hornworts and liverworts in the wider estate and the garden. Lacking true roots and vascular tissues, this extraordinary, ancient group of plants absorb water and nutrients through their surfaces instead and reproduce through spores rather than seeds. They’ve been living on earth at least 75 million years before the age of the dinosaurs and play an important role in ecosystems. They are often the first species to colonise bare rock or disturbed ground, kickstarting soil creation by trapping dust, breaking down rock and creating organic matter. This process creates microhabitats that supports small organisms that in turn are food for those larger organisms further up the food chain, as well as providing nesting material for birds, amphibians and small mammals. That organic matter traps and recycles nutrients that would otherwise be lost – in the case of peat moss, acting as a major carbon sink. They form mats that prevent soil erosion and help regulate and slow water, acting like sponges, absorbing and storing moisture, and can be used to monitor air quality as they are sensitive to pollutants like sulphur dioxide and heavy metals. Since they absorb nutrients and water from the air, not through roots, a decline in species diversity and abundance or absence of sensitive species can be an important tool in urban planning and pollution monitoring.

With over 15,000 species worldwide (1098 in the Uk and Ireland), they can occupy a much wider diversity of habitats than the flowering plant kingdom, from caves to tall trees, frozen tundra to blazing desserts.

The Sussex Bryophyte Society found the surrounding walls of the garden well covered in mosses, finding “no rarities, but a nice selection of common wall mosses” and were intrigued to see what communities grew on the three ancient olive trees in the hot Mediterranean corner by the swimming pool, a substrate they don’t encounter very often. (Small hairy screw-moss, forked veilwort and dilated scalewort!). The dry, warm days this month meant identifying some of the ground-dwelling species was tricky, their characteristic features shrivelled. Still in winter mode, only a few of the surveyors had brought rehydrating spray bottles, but they managed a good count of the more distinctive species. We hope to gain a comprehensive list from them in time so that we can expand our knowledge and continue to monitor this fascinating family of plants.

It seems counterintuitive to find that so much moss has formed on Hitchmough Ridge, as we affectionately call it – the most free-draining area of the Rewilded Garden – but the porous nature of concrete allows for rhizoids (the tiny anchoring threads the bryophytes have in place of roots) to penetrate its surface, no doubt aided by the excessive rains of last year. Different species of moss grow according to the acidity of the substrate. Concrete is generally alkaline (or ‘basic’) and the constituent cement often contains limestone. But our crush mix also contains ‘acidic’ brick aggregate from demolished farm buildings taken from the Wilding Kitchen site when we re-landscaped the garden back in 2021, encouraging a wider spectrum of bryophytes. Their spores are incredibly tiny and light – they’ve been estimated to travel more than 12,000km through high-altitude air currents. Now that this range of colonising mosses has established on the ridge, they have helped shift the habitat to favour other moisture-loving species.

Our maintenance of the garden, however, is driven by the aim of supporting as many habitats and plants as possible, and this means providing as wide a range of soils as we can, from dry to damp, from poor to nutrient-rich. The moss smothering the surface was beginning to change the conditions for all the xeric plants we’ve sown and planted here. So, we worked through the ridge disturbing the ground, removing large areas of moss, exposing the aggregates and sand to awaken seeds to germination, while still retaining some mossy islands of green for insect habitat and nesting material.

All through the Kitchen and Rewilded Garden we have cleared and planted areas with a new array of edible and pollinator-friendly plants, extending the range and services for wildlife. For the bowl of the ephemeral pond, we’ve added two resilient, long-flowering taller species – red bistort (Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Rosea’) and giant fleabane (Inula magnifica) – that flower in summer and into autumn, to attract butterflies, bees and other pollinators. With many of the same attributes, the toad lily (Tricyrtis ‘Hototogisu’) thrives in dry shade, its purple spotted, orchid-like flowers filling the hungry gap for pollinators in the autumn. The pure white plumes of false goat’s beard (Astilbe x japonica ‘Deutschland’) supply nectar at the other end of the season, in late spring and early summer. Planted in the shadier spots, its luminous quality is particularly attractive to butterflies. Incidentally, it’s also deer resistant, if you have a garden that is accessible to fallow or roe deer. Both magnets for bees, gentian speedwell (Veronica gentianoides) and rose campion (Lychnis coronaria) have new homes in what was formerly Acacia Walk, the section that joins both gardens, where we’ve had some compaction issues. In habit they are mat- and clump-forming and can cope with the poorer conditions and will put roots down to improve soil structure as well as fill the space with gentle blues and magenta pinks.

Two of the edible additions in the Kitchen Garden are Chinese mahogany (Toona sinensis) and viper’s bugloss (Echium vulgare ‘Blue Bedder’). The first is an Asian fast-growing tree that can eventually reach 40 metres (although we will manage its growth!). Sometimes called the beef and onion plant, the young onion-smelling leaves are used extensively in Chinese cooking and as a flavouring paste. The second, so named because it was once thought to remedy the effects of a viper’s bite, has many medicinal properties as well as being rumoured to stimulate sexual desire. The leaves have a low toxicity and can be a skin irritant but historically they were used in small amounts as a spinach substitute. We’re growing it predominantly for its intense blue flowers and, since it’s a native plant, its services to native insects. From the same family (Boraginaceae) we’ve planted Italian bugloss (Anchusa azurea ‘Loddon Royalist’) whose edible cobalt-blue flowers can add an intensity to salads or be suspended in ice cubes in a summer punch. In all, 50 new species have been planted between last autumn and this spring to bring our total to 1,062 species from 112 different plant families in the garden.

This range and diversity of plants was a subject that Suzi and I highlighted in a talk we gave at the London Gardeners Network seminar on ‘Growing Communities of Resilience, Come Rain or Shine’. With the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicting that for every degree rise in temperature the climate envelope will move northwards by 150km (or 150m in altitude), a garden’s resilience will be greater, the broader the range of plants, above- and below-ground biomass, flowering times, water retention features and structural complexity it has. We spoke about the undulating topography and the bowl of the ephemeral pond in the Rewilded Garden acting as reservoirs for rainfall and slowing and holding water; the benefits of including plants accustomed to harsh conditions that hail from extreme habitats such as dry stony riverbeds, American prairies and mountain scree; and building resilience into food growing by focusing on less thirsty, time- and resource-heavy perennial vegetables, and broadening our palettes to include unconventional alternatives in our diet.

Other speakers on the day included the brilliant Wendy Allen, innovative designer and consultant on rain gardens and planters, who is a firm believer that no rainwater need ever end up in a drain when it can be slowed, absorbed, taken up by plants or harvested. The panel discussion moved between the role of AI in horticulture (surely another whole seminar in the making), how to accommodate extreme rainfall occurrences into landscape design and local government planning in public spaces and transport systems, and how broader education might engender a mindset change towards rainfall being an opportunity rather than a problem.

A big takeaway for us was the importance of monitoring and data collecting. We’ve recorded data on soil and wildlife in the garden since we conducted baseline surveys in 2020. We’re also building a picture of the hours spent maintaining the garden – as an experiment, is a garden designed to cope with the challenges of climate change sustainable in terms of manpower? The seminar highlighted our lack of recording on the climate in our area – the specifics of weather, flooding, drought and storms in our own green space. It’s only by building up records of how a changing climate impacts an ecosystem over time that we’ll be able to respond with nature-based solutions.

Meanwhile, the first stork egg of the season is laid, wild cherry blossom bursts from the hedgerows and the fuzzy yellow rabbit-tails of willow catkins break out next to fat buds held on naked horse chestnut stems. The greenhouse is pregnant with seedlings and trays of sown seed, all around us, life emerging, exuberant and joyful.

Photos courtesy of Joshua Chalmers, Jenny Seawright

Visit the Walled Garden. Find out What’s On at Knepp including our Self-guided walled garden tours, Rewild Your Vegetable Garden and Market Garden workshops.

What we’re reading:

Sussex Bryophytes | Mapping the mosses and liverworts in south-east England

Knepp Castle Estate | Sussex Bryophytes

About bryophytes – British Bryological Society

Moss gardening – British Bryological SocietyBryophytes – AZ Index

Roles of Bryophytes in Forest Sustainability—Positive or Negative?

(PDF) Ecological and Economic Significance of Bryophytes

LGN Spring Seminar 2025 — London Gardens Network

Pastry/Prep Chef Salary: £30,000-£33,000 (excluding tips) Tips: Approx. £800+/month Hours: 45 hours per week over five days Location: Knepp Wilding Kitchen, Dial Post, RH13 8PY

Junior Sous Salary: £33,000-35,000 (excluding tips)Tips: Approx. £800+/monthHours: 45 hours per week over five daysLocation: Knepp Wilding Kitchen, Dial Post, West Sussex, RH13 8PY The

Seasonal Breakfast Chef Salary: 6 month pro rata, £30,000 Tips: Approx. £800+/month Hours: 45 hours per week over five days Location: Knepp Castle Estate, West

Knepp Wildland Safaris, our gardens and campsite are all about the quiet and patient observation of nature.

Some of the species we are likely to encounter are shy or can be frightened by loud noises or sudden movements. Our campsite with open-air fire-pits, wood-burning stoves and an on-site pond is unsuitable for small children.

For this reason, our safaris, garden visits, holiday cottages and campsite are suitable only for children of 12 and over.

You’ll receive relevant offers and news by email. This will include information about the Rewilding Project, online store products, the Wilding Kitchen Restaurant / Cafe, and other exciting experiences / events across the Knepp Castle Estate. For more information, view our Privacy Policy.